Rethinking Freedom in the Age of Technology

Defining Independence in an age of digital dependence

On the occasion of India’s Independence Day, I found myself reflecting on what independence means today. In 1947, independence was about liberation from colonial rule, the right to self-determination, and the ability to chart our own destiny as a people. Seventy-nine years later, the tricolour still carries that resonance of freedom and dignity.

But in our digital century, independence has taken on a new dimension. While we remain politically free, we live in a paradox: we are increasingly dependent on technology. Our communication, our mobility, our finances, our healthcare, even our social lives now run on digital systems that we neither fully understand nor fully control. This dependence is not unique to India. It is the story of our interconnected world. It raises a pressing question:

What does independence mean in the age of algorithms and data-driven systems?

Independence and Dependence in the Digital Era

Political independence gave us the power to govern ourselves. Digital dependence, by contrast, risks shifting that power into the hands of technological infrastructures that are often global, opaque, and monopolised.

This is not to demonise technology. Dependence is not always negative. Our lives are richer, faster, and in many cases safer because of it. From mobile payments to telemedicine, from satellite weather forecasts to e-commerce, technology has expanded what individuals and societies can do. But independence, in its truest sense, is about choice. And if our choices are increasingly mediated through invisible systems, we must ask whether we are still as free as we imagine.

Industry 4.0: From Mass Production to Personalisation

We stand today in the midst of what is called Industry 4.0. The first industrial revolution mechanised labour, the second electrified mass production, the third brought computation and automation. The fourth is defined by connectivity and personalisation.

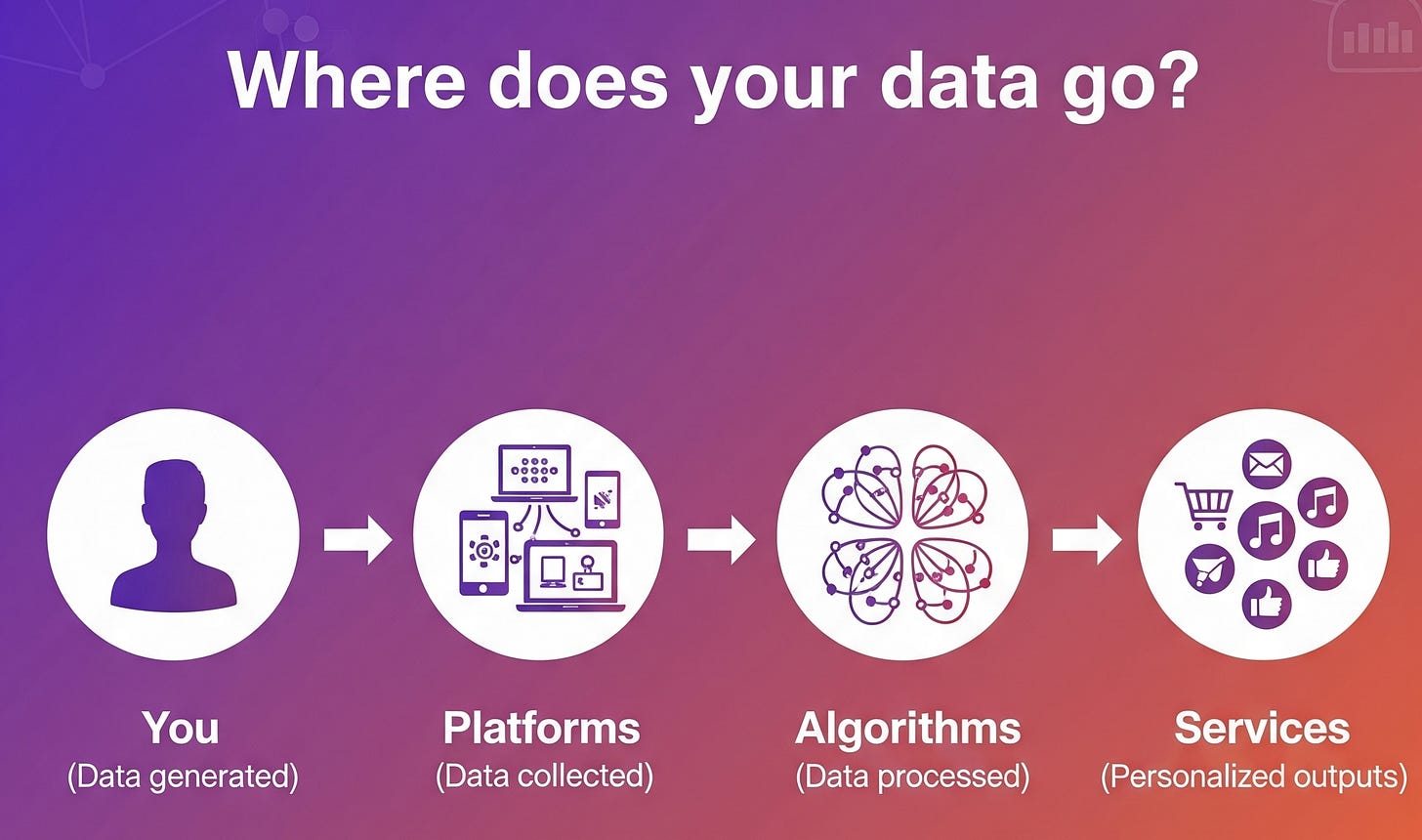

Industry 4.0 thrives on data. The more information it has about us, the more it can personalise services, anticipate needs, and offer convenience. This is why our feeds feel tailored, why our navigation apps seem intuitive, why digital platforms know what we might buy next. Personalisation has become the defining feature of modern digital life.

But this personalisation comes at a cost. It requires constant surveillance of our behaviours, preferences, and networks. It turns data into the new raw material of the global economy. And when control over that data is concentrated in a few corporate or state actors, power itself becomes centralised.

The Question of Data Governance

This brings us to the idea of data governance. Who owns the data we generate? Who has the right to use it? How do we hold platforms accountable for the ways they collect, process, and profit from our lives?

India has taken steps with the Digital Personal Data Protection Act. The European Union has set global benchmarks with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). These legal frameworks matter. But governance cannot be left to policymakers alone. Citizens need to be part of the conversation.

Data governance is not just about compliance. It is about awareness and agency. Without literacy, laws remain distant and abstract. With literacy, people can ask the right questions, demand transparency, and make informed choices about what they share and what they protect.

Literacy as the First Layer of Independence

Tech literacy is often confused with the ability to use tools. But knowing how to use an app is not the same as understanding how that app uses us. True literacy goes deeper: it means recognising the economic models behind free platforms, the biases embedded in algorithms, and the vulnerabilities created by centralisation.

Globally, there are inspiring examples. Estonia has built one of the most digitally literate societies, where citizens interact seamlessly with government systems while retaining rights over their data. Kenya’s M-PESA transformed financial access, not by imposing foreign models but by building digital infrastructure aligned with local needs. In Europe, public debates around AI have given citizens a stronger voice in how new technologies are deployed.

For India and the world, the lesson is clear: literacy is the first step toward resilience. A literate citizenry cannot be so easily manipulated by misinformation, monopolised by platforms, or excluded from participation.

The Convenience–Control Paradox

Yet literacy alone is not enough. Technology is seductive because it is convenient. We use maps because they guide us effortlessly, streaming platforms because they save us time, digital wallets because they make transactions frictionless. Delegating to machines is natural.

The danger arises when convenience eclipses control. Just as pilots risk losing manual flying competence if they over-rely on autopilot, societies risk losing civic and critical competence if they outsource too much to algorithms. This is not just about privacy, but about capacity. Do we still have the ability to think, decide, and act independently when the systems around us automate choice itself?

Participatory Design vs Monopolised Systems

If literacy is the foundation, participatory design is the next layer. Participatory design means involving people in shaping the very technologies that shape them. It is about moving from being passive consumers to active co-creators.

Contrast this with the current reality. A handful of technology giants—Google, Meta, Amazon, Tencent—sit atop massive data monopolies. They provide services that billions rely on, but their models are extractive. Value flows upward, while agency flows downward. Monopolisation of data not only stifles competition, it also reduces the space for public participation.

Decentralised systems offer an alternative. Public digital infrastructure, such as India’s Aadhaar-enabled payment systems or the Unified Payments Interface shows how platforms can be designed as open, interoperable layers rather than monopolised services. Similarly, federated models of AI, blockchain protocols, and open-source ecosystems offer ways to distribute control rather than concentrate it.

Participatory design does not mean everyone becomes a programmer. It means citizens have a voice in setting the rules, communities can shape technologies to local needs, and governments act as enablers rather than gatekeepers. It is about building systems with society, not just for society.

Building Resilience Through Decentralisation

The deeper reason participatory and decentralised models matter is resilience. Centralised systems are efficient, but brittle. When a single platform dominates, its failure—or misuse—can have global consequences. We have seen this with social media misinformation, with outages in cloud services, and with geopolitical conflicts over digital supply chains.

Resilient societies need decentralised infrastructures, where failure in one part does not collapse the whole. They need open standards, where innovation can flourish without dependence on a few gatekeepers. And they need empowered citizens, who can adapt and participate rather than passively consume.

Just as political independence required distributed struggle and shared vision, digital independence requires distributed systems and shared participation.

As India celebrates 79 years of freedom, we honour a generation that redefined what independence meant in their time. Our generation faces the challenge of redefining it in ours.

Independence is no longer just political. It is digital, social, and participatory. It is about the right not just to access technology, but to shape it. It is about balancing convenience with control, literacy with agency, personalisation with transparency. Above all, it is about resisting the drift toward monopolised dependence and choosing instead to build resilient, decentralised systems that empower communities worldwide.

The story of 1947 teaches us that independence was not granted—it was earned. In the same spirit, digital independence will not arrive by default. It will be earned by citizens who are literate, by systems that are participatory, and by societies that choose resilience over monopoly.

The question is not whether technology will shape the future. The question is: Will we shape it together, or allow it to be shaped for us?